An approach to digital humanities

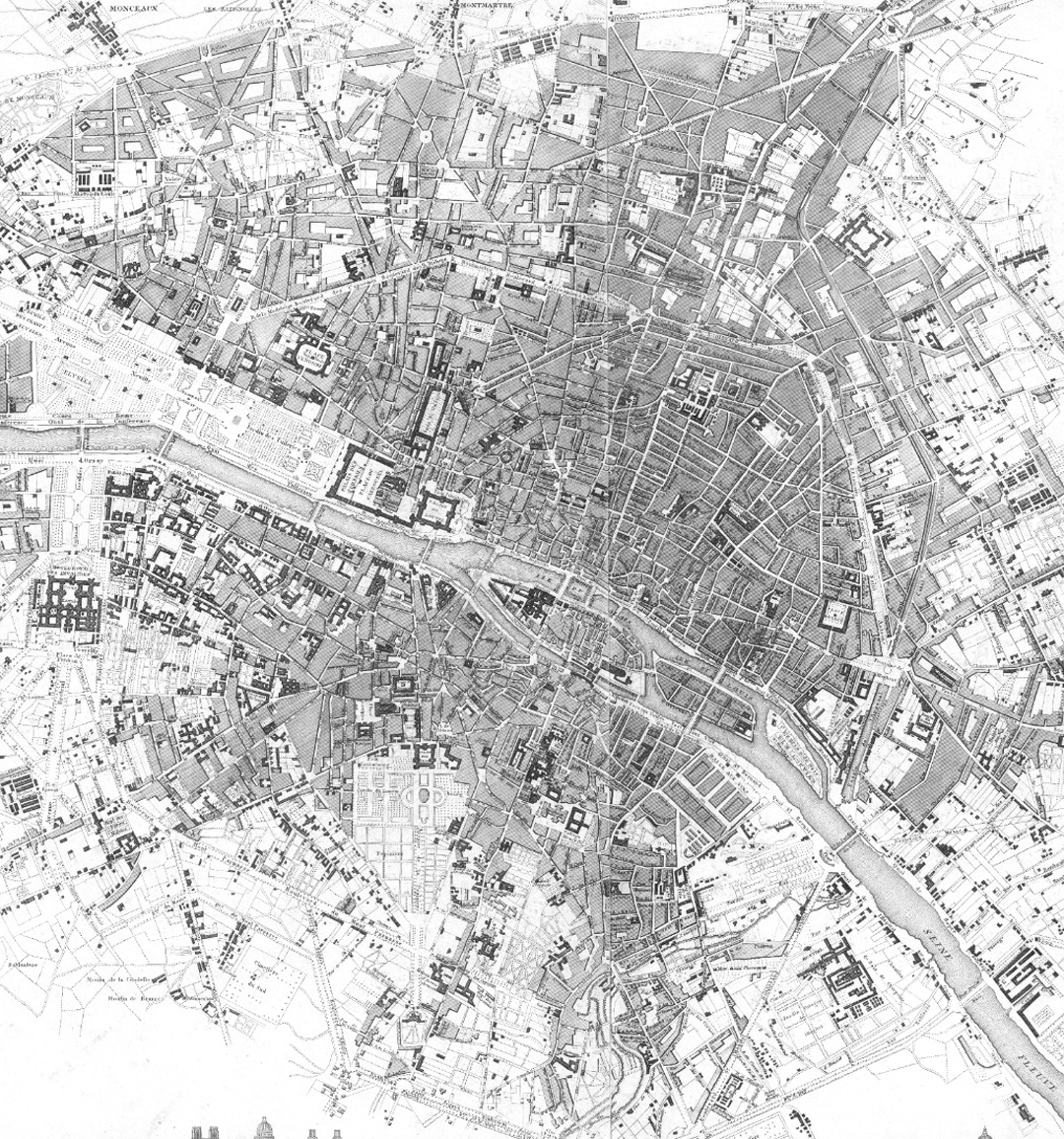

“Mapping Paris” is a historical and literary research project that investigates, through data analysis, the relationships of meaning between cultural events and geographical space in nineteenth-century Paris. This project facilitates the sharing of open data for the historical, sociological and literary investigation of Paris and opens up to the collaboration of those who want to contribute to research.

Projects work 1

Mapping the “vie littéraire” of Goncourt brothers in Paris during the Second Empire

Projects work 2

The revenues of Parisian playhouses in the theatrical life of the Second Empire (1858-1867)

Projects work 3

Projects work 4

Paris from Stendhal to Maupassant

Mapping the “vie littéraire” of Goncourt brothers

in Paris during the Second Empire

.

Michele Sollecito, Mapping the “vie littéraire” of Goncourt brothers in Paris during the Second Empire. An approach to digital humanities, Palermo, 40due edizioni, 2019.

Michele Sollecito, Roberta De Felici

(ed.), Edmond et Jules de Goncourt,

Théâtre, Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2021

Contact

Michele Sollecito is a researcher in French literature at the University of Bari “Aldo Moro”.

He studied dramatic criticism in nineteenth-century France, with a particular focus on the theatrical works of the Goncourt brothers (Paris, Classiques Garnier 2021). He holds a master’s in Digital Humanities from the University of Venice “Ca’ Foscari”.

Contact Details

michele.sollecito@uniba.it

@mikesolle